Introduction

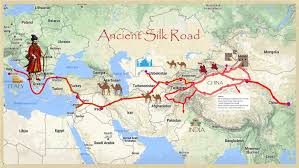

The Silk Road was a very large network of trade routes across Asia. It was active for a very long time, from around the 200s BCE until the 1400s CE. This network, which was over 6,400 kilometers long, was extremely important for connecting the Eastern and Western parts of the world. It allowed for the exchange of goods, culture, religion, and ideas. The name “Silk Road” was created in the 1800s, but many modern historians like to use the term “Silk Routes” because it better describes the complex web of both land and sea paths (Wikipedia).

What Was the Silk Road?

The Silk Road was not one single road. Instead, it was a system of many different routes. These routes connected Central Asia, East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, West Asia, East Africa, and Southern Europe. One major southern land route, known as the Karakoram route, went from China through the high Karakoram mountains. This path is followed today by the modern Karakoram Highway between Pakistan and China. It then moved west into Afghanistan and Turkmenistan (Wikipedia).

Because of its work preserving important global sites, UNESCO has declared parts of the Silk Road as World Heritage Sites. This includes the Chang’an-Tianshan corridor in 2014 and the Zarafshan-Karakum Corridor in 2023. Other sections are being considered for this special status (Wikipedia).

Afghanistan: The Heart of the Silk Road

Afghanistan’s location made it very powerful and wealthy in ancient times. It sits in the center of Asia, where many Silk Road routes met. Routes went east to China, north to cities like Samarkand, southeast into India, and west into Iran and Europe. Because almost all trade between these areas had to pass through Afghanistan, its cities became rich and important trading centers (UNAMA).

Afghanistan’s role in trade is very old. For example, the famous blue lapis lazuli stone in Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun’s funeral mask from 1300 BCE came from Afghanistan’s Badakhshan region. Even earlier, around 2500 BCE, this stone was sent to Iraq. By the 2nd century BCE, trade routes reached China. A Chinese traveler, Zhang Qian, visited northern Afghanistan in 130 BCE and described the people as clever traders with busy markets (UNAMA).

Key Afghan Regions and Cities:

Several Afghan provinces and cities were critical hubs:

- Balkh (Ancient Bactria): Known historically as Bactria, this was a vast and powerful ancient region. Its capital, Bactra (modern Balkh), was a major political and commercial center and a terminus for silk from the east. The region was bordered by the Amu Darya river to the north and the Hindu Kush mountains to the south.

- Herat: This ancient city, known in historical texts as Haroyu or Aria, was a cultural and economic crossroads. Before the discovery of sea routes to the Indian Ocean, Herat was a vital passageway for trade between India, the Middle East, Central Asia, and Europe (esalat). It was so renowned it was once called “the pearl” of the region. It served as a key distribution point where silk from Balkh would move towards Mashhad, Tehran, and Turkey.

- Badakhshan: This province was a major cultural and commercial junction on the Silk Road, neighbored by China, Transoxiana, and Pakistan. Famous for its precious stones like lapis lazuli and rubies, it was also a central silk route. Eastern roads like the Wakhan and Khatan (Marco Polo route) passed through specific crossings like Khatl, Jaryab River, and Vakhshab on their way to Balkh. The province’s geography—with deep valleys and narrow passes—made it both a challenging transit zone and a refuge for many groups. Its history of commercial exchange is evidenced by the common finding of silk pieces there and its enduring reputation for cocooning and silk production (esalat).

- The Wakhan Corridor: This high-altitude valley in northeastern Afghanistan (Badakhshan) served as a direct geographic link to China, with passes like the Wakhjir Pass connecting the two regions.

- Bamiyan Valley: In the early 7th century, the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang embarked on a historic pilgrimage to India via the Silk Road. This ancient network carried more than silk and spices; it was a vital channel for ideas and faith. Arriving in Afghanistan’s Bamiyan Valley, Xuanzang found a thriving monastic center. His most famous account describes the valley’s two colossal Buddha statues carved into a cliff. He recorded that the larger statue, over 50 meters tall, was “adorned with golden color and brilliant gems,” while its 35-meter companion shone with silver. His detailed observations of their glittering, bejeweled splendor provide the most significant historical record of their original majesty. Centuries later, Xuanzang’s vivid description stands in stark contrast to the empty niches left after their 2001 destruction, preserving a vital memory of the Silk Road’s lost cultural wonders.

- Other Major Centers: Kabul were also strategically located on the trade routes, benefiting from the flow of goods and ideas.

Cultural and Economic Exchange

The Silk Road was about much more than just goods. It was a highway for culture and religion. Buddhism spread from India to Afghanistan and then on to China, with the giant Bamyan Buddhas standing as proof of this influence. Chinese designs later influenced Islamic architecture, and Mongol ideas affected Afghan laws. Elements like traditional hospitality and the many languages spoken in Afghanistan today are lasting cultural impacts from this period (UNESCO).

Goods traded through Afghan cities included Chinese silk, Persian silver, and Roman gold. The period from the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE was a high point, especially under the Kushan Empire, which controlled much of Afghanistan and surrounding areas (UNAMA).

The Four Powerful Empires

For centuries, the Silk Road flourished due to four powerful empires. The Han Dynasty in China secured the eastern routes. The Kushan Empire blended cultures as middlemen. Parthia controlled the central part of the roads, taxing trade with its cavalry. At the western end, the Roman Empire pursued maritime trade when land routes were blocked (The Controller).

Decline of the Silk Road

The Silk Road began to lose importance after its peak. Several reasons caused this decline. First, sea routes became safer and cheaper than the dangerous overland paths. Political instability, wars, and banditry made travel difficult. The Ming Dynasty in China closed the eastern end, and the fall of Constantinople in 1453 changed trade control. European powers, seeking new routes to Asia, began the Age of Exploration. This eventually led to a sea route around Africa, making the old Silk Road less necessary (EBSCO).

Archaeological Evidence

Archaeology proves the Silk Road’s ancient history. In Uzbekistan, an academician named A.A. Askarov found pieces of silk clothing in tombs from 1700-1500 BCE (UNESCO). He also discovered that bronze vases from Central Asia were identical to vases found in museums in China (UNESCO). These findings show that trade connections between China and Central Asia existed long before the official Han Dynasty missions (UNESCO).

Lasting Impact and Modern Revival

The Silk Road left a deep mark on Afghanistan, most visibly in its rich diversity of cultures, tribes, and religions that exists to this day (UNESCO).

In modern times, there is a major effort to revive the spirit of these routes. In 2013, China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a huge project to build new trade and infrastructure networks across Asia, Europe, and Africa. It includes a land-based “Silk Road Economic Belt” and a sea-based “21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” aiming to boost trade and growth (Investopedia).

Reference

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silk_Road

- https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/countries-alongside-silk-road-routes/afghanistan

- https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/default/files/knowlege-bank-article/New Discoveries on Ancient Silk Road.pdf

- https://unama.unmissions.org/en/node/59870#:~:text=Goods wanting to pass between,as places of mercantile exchange.

- https://www.thecollector.com/four-empires-silk-road/

- https://www.theglobalist.com/the-silk-road-a-romantic-deception/

- https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/silk-route.asp

- https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/decline-silk-road

- https://www.lifelonglearningcollaborative.org/silkroads/articles/xuanzang-on-the-silk-road.html

- https://www.esalat.org/images/afg_jada_abrishom_ustad_sabah_0362015.htm

Let’s Go Afghanistan Team